If you have any interest in that revolutionary era of our country’s history you will probably enjoy this book.

Saturday, October 15, 2016

Cluster Critiques

Before the Fall by Noah Hawley

Before the Fall is a B+ suspense novel that

unflinchingly patronizes us with character clichés. There’s the failed but handsome

male artist, unwilling to compromise his talent in the face of poverty and alcoholism,

the pristine pre-school teacher uncorrupted by her marriage to a predictably

slimy media magnate, said slimy media magnate, his even slimier investigative

journalist, and Wall Street broker, a beautiful and too-hip “trustafarian”, an

abused good-hearted wife, and a perfect little 4-year-old boy.

Author

Hawley (who I should mention is a very successful writer of the “Fargo” TV show)

opens with most of these characters boarding a private plane, and immediately

and effectively punts our curiosity up to wide-eyed volume. What’s going to

happen? We find out pretty quickly when, 18 minutes into the flight, the plane

goes down, the only survivors being the artist and one of the teacher and media

magnate’s two children.

In spite of

his corny characterizations, Hawley does a commendable job of moving the plot

along, which includes possible terrorists involvement (wow what a surprise),

icky backroom politics (now that’s a unique plot twist), journalistic

sensationalism (really?), the hero’s struggle with the seduction of sex,

alcoholism and money (so original), and the heart-warming resilience of

children (yep, that too), to the point that this reader eventually just wanted

to throw the book across the room. But I didn’t, and you probably won’t either.

After

slogging through Before the Fall I saw a description that said it was “an exploration of the

human condition, a meditation on the vagaries of human nature, the dark side of

celebrity, the nature of art, the power of hope and the danger of an unchecked

media” and I just felt so cheap.

All Things Cease to Appear: A Novel

by Elizabeth Brundage

Since I’m

on an admittedly unentitled hypercritical roll, I’ll roll over on Elizabeth

Brundage’s most recent effort, All Things

Cease to Appear, another collection of boilerplate characters that promises

an interesting story, but doesn’t pay off. I would have tossed

this one for sure, but it was a book club choice, so I had to finish it.

Asshole, unethical, entitled professor marries gracious, naïve girl then moves

them all to an isolated country home, which happens to be the setting of a

previous, macabre murder.

Brundage

leads us right up to the cliff of intrigue

- a possible ghost story, possible romance, possible psychosis, possible

revenge, but she never pushes us over the cliff, and we just stand there

waiting and waiting for the plot to plunge us into a really compelling,

surprising story, and it just doesn’t happen. I really wanted to like this

book, which could have been good but just wasn’t.

The

Doctor’s Wife by Myra Hargrave McIlvain

Austin writer Myra Hargrave McIlvain’s book, Steinhouse, was one of my favorites in

2015. Having written many of the Texas roadside historical markers and much

about Texas history, McIlvain has a deep and detailed dossier of material from

which to draw her novels. But knowledge alone doesn’t create

readable history. What makes McIlvain’s writing so readable is her

extraordinary skill at extracting historic detail and weaving that with

realistic, compelling characters to create stories that resonate with

believability, cultural intrigue and adventure.

In The

Doctor’s Wife, Ms. McIlvain tells the story of a young German girl who

sails to Texas in the mid 1800’s, following the promise of the Adelsverein, a group of German noblemen committed to

establishing a “new Germany” in Texas – including New Braunfels, Fredericksburg

and many other communities. Upon arriving in Galveston, Amelia Anton had no

reason to be there. The young son she’d been hired to tutor has died, not

uncommonly, on the long voyage from Germany to Texas. Separated from her

family, young, and isolated in a land raw with the turmoil of slavery and war

with the Comanche Indians and the Mexicans, both of which were fighting off the

American claims for Texas, Amelia goes to work in Galveston’s Tremont Hotel,

cleaning and emptying chamber pots. Fortune finds her it seems, when she meets

Dr. Joseph Stein, who takes Amelia as his wife and moves her to another Texas

coastal town, Indianola, where he is desperately needed to help other German

immigrants who are ill, stranded and waiting for safe passage to inland German

communities.

What a blessing it seems for

Amelia to become the wife of the handsome Dr. Stein, but we soon find that in

addition to the extremely difficult lifestyle of primitive Indianola and early

Texas settlement, Amelia is faced with a loving but agamous marriage. Desolate

and confused, Amelia struggles to reconcile her relationship, finally finding

love on a beautifully told adventure to New Orleans, which sadly ends in

tragedy.

The reader turns each page

looking for hope for Amelia, for the German settlers, for Texas, and even for

Dr. Stein and his lover, Hans, all the while luxuriating in the sights, smells

and sounds of the Texas coast, Galveston and New Orleans, as so

elegantly and sharply penned by the author.

A dreadful smell grew stronger as their

carriage neared the French Market, a broad low roof covering an arcade of open

stalls. Next to the street, feathers flew from the hands of black children

plucking chickens. Women tossed the guts into the drain moving sluggishly along the street. Vendors waved long, thin loaves of bread. A multitude of

fruits and vegetables piled high on tables, and the aroma of coffee blended

with a cacophony of languages.

The best of historic novels put us in a significant

era of history, and in the spirit, passion and tragedy of the characters living

that history, like Margaret Mitchell’s Gone

With The Wind, Kathleen Winsor’s Forever Amber, and Myra

Hargrave McIlvain’s The Doctor’s Wife.

Ms. McIlvain has written an intriguing story about Texas history, in the

context of particularly unconventional plot twists, and about characters for

whom we grow to care.

A

Gentleman in Moscow: A Novel by Amor Towles

A voracious reader, my mom probably read Nobel

Prize winner Boris Paternak’s novel Dr.

Zhivago before it became a multi-Academy Award winning movie in 1965,

starring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif. And I suspect both had something to do

with inspiring her to travel to Russia in 1967 with a group of teachers, when

practically no one went to Russia, and the shadow of the cold war and Cuban

Missile Crisis still very much defined that country. Dr. Zhivago is the story of a physician and poet, set during the

Russian Revolution of 1917.

A

Gentleman in Moscow is about Count Alexander Rostov a former

aristocrat in The Russian Empire, who, having been accused of writing an

anti-revolutionary poem, is sequestered for life by the Bolsheviks in

one of the last bastions of pre-Bolshevik luxury, the Metropol Hotel. The

Washington Post astutely claims, “In an era as crude as ours…‘A Gentleman in Moscow’ is a charming

reminder of what it means to be classy.” And classy it is.

As

with his previous novel, “Rules of Civility”, in A Gentleman in Moscow we become enraptured with the poetry of Amor

Towles writing, which feels

like good sex on real satin sheets with Lead Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love playing in the background. Unlike “Rules of

Civility” we are also enraptured by the story – or perhaps more accurately, Count

Rostov enraptures us. I want him to be my daddy, my husband, my child, or maybe

just a distant uncle, for there was never before or since, anyone as cool as

Count Rostov. Alexander Rostov turns imprisonment, albeit fairly luxurious

imprisonment, into a fulfilling life well lived. The Count befriends the hotel

chef and conspires for years in a country destitute of food, to collect the

ingredients for a single night of Bouillabaisse. He beguiles and beds a famous

Russian actress. He raises the child of a woman he met in the hotel when she

was a child herself. He accomplishes amazing feats – the final of which

constitutes one of the best book finishes I’ve ever encountered – all within

the confines of a hotel. Here are a few Count Rostov observations that speak to

his, and this book’s, allure.

Count Alexander Ilyich

Rostov stirred at half past eight to the sound of rain on the eaves. With a

half-opened eye, he pulled back his covers and climbed from bed. He donned his

robe and slipped on his slippers. He took up the tin from the bureau, spooned a

spoonful of beans into the Apparatus, and began to crank the crank. Even as he

turned the little handle round and round, the room remained under the tenuous

authority of sleep. As yet unchallenged, somnolence continued to cast its

shadow over sights and sensations, over forms and formulations, over what has

been said and what must be done, lending each the insubstantiality of its

domain. But when the Count opened the small wooden drawer of the grinder, the world

and all it contained were transformed by that envy of the alchemists—the aroma

of freshly ground coffee. In that instant, darkness was separated from light,

the waters from the lands, and the heavens from the earth. The trees bore fruit

and the woods rustled with the movement of birds and beasts and all manner of

creeping things. While closer at hand, a patient pigeon scuffed its feet on the

flashing.

Whether through careful consideration spawned by books and

spirited debate over coffee at two in the morning, or simply from a natural

proclivity, we must all eventually adopt a fundamental framework, some

reasonable coherent system of causes and effects that will help us make sense

not simply of momentous events, but of all the little actions and interactions

that constitute our daily lives–be they deliberate or spontaneous, inevitable

or unforeseen.

“It is not the business of a

gentleman to have occupations.”

The

Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo by Amy Schumer

I can only tolerate about 3 minutes of Amy

Schumer in one of her stand-up shows, or in a movie, but I really liked her

book, The Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo,

which obviously is her humorous twist on the book The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Here’s why I like Amy’s book.

First, she comes across as much more intelligent and funny in her book. Second,

she has been taking really good care of her father, who has been living in

assisted living for more than 20 years due to multiple sclerosis. Third,

Amy, a victim of relationship abuse and sexual assault, has taken a vocal

position urging re-thinking about what constitutes consensual sex. And finally,

she and I are both introverts. I know, I know. No one believes I’m an introvert

either. I totally got her description of having to cocoon occasionally – to

isolate herself to recover from over stimulation.

The one thing I don’t get about Amy is her seeming

refusal to forgive her mother, who she previously idolized, for having an

affair with her best friend's father. It seems humans tend to be much more sympathetic

of people from whom we have little expectations, and less sympathetic of people

from whom we expect much.

The

Girl with the Lower Back Tattoo is good enough, and was for

me, an interesting study in Schumer’s generation.

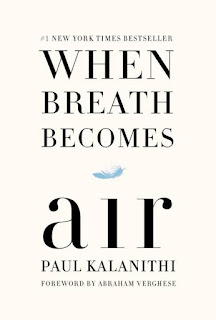

When

Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

Dr. Paul

Kalanithi couldn’t decide whether to be a brain surgeon or a writer, so he did

both, very, very well. When Breath

Becomes Air is Kalanithi’s story of finding out he had lung cancer (he was

not a smoker) and dying, at the age of 37.

As with Lao Tzu’s proclamation, “The flame that burns twice as bright burns half

as long,” Kalanithi had two BA’s and an MA in literature from Stanford, a

Master of Philosophy at Cambridge, and graduated cum laude from the Yale School

of Medicine, returning to Stanford for a

residency in neurosurgery and a postdoctoral fellowship in

neuroscience.

When first finding out about his

cancer, his “Dr.” instinct is to research, to pinpoint the probability of

living a year or a month – what he would do for his own patients facing death.

But what he discovers is that how long a dying person has brings no comfort.

“What patients seek is not scientific knowledge that doctors hide, but

existential authenticity each person must find on her own … the angst of facing

mortality has no remedy in probability.”

Seems there are lots of books written by and about

people who are dying but I doubt you’ll find one more beautifully written, nor

one with this special insight of a doctor treating the dying, who then himself becomes

the dying. “I had

pushed discharge over patient worries, ignored patients’ pain when other

demands pressed. The people whose suffering I saw, noted, and neatly packaged

into various diagnoses, the significance of which I failed to recognize — they

all returned, vengeful, angry, and inexorable.”

American

Heiress: The Wild Saga of the Kidnapping, Crimes and Trial of Patty Hearst by

Jeffrey Toobin

Several

generations remember where they were the day John Kennedy died, as do I. I also

remember the moment I saw this photo of Patty Hearst on TV in 1974. I was a

young mother living in the wilds of west Texas, about as removed as possible from

that distinctly revolutionary period in our country’s history. I remember

thinking, “Why would a small group of people take such legal risks just to be heard?” and “Why would someone kidnapped by a radical group take up their

banner?” It all just seemed so far away from my reality, and so radical, and

absurdly attractive for reasons I didn't understand.

Then I

completely forgot about Patty Hearst and the Symbionese Liberation Army until 1981

when I was hired to manage a ranch in New Mexico and was told the ranch was

formerly a survivalist commune and suspected hideout of the Symbionese Liberation

Army, which was under surveillance by the FBI, trying to find Patty Hearst.

So

basically, I have two pretty strong points of reference to Jeffrey Toobin’s

book about the incident of Hearst’s kidnapping and eventual conviction of

charges stemming from her collusion with the Symbionese Liberation Army in

their various illegal activities, including bank robberies, kidnappings, attempts

to bomb a police car and other similar activities.

Without a

doubt, The New Yorker staff writer

Toobin’s a smart guy (magna cum laude graduate of

Harvard Law School), and although I’ve only read one other of his books The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, which I thought was quite

good, because I have an abiding curiosity about Patty Hearst, of course I had

to read this book.

At the time of her kidnapping Hearst was a student

at Berkeley, living with and engaged to one of her professors, and somewhat

estranged from her parents – descendants of the legendary Hearst newspaper

clan. The Symbionese Liberation Army was a small cell of left-wing

revolutionaries, not uncommon during the politically tumultuous 1970’s. Just as

they’d hoped, kidnapping a somewhat celebrity tied to a family with deep

pockets, brought more recognition to their organization than practically

anything else would have.

From that point forward, the story differs,

depending upon whom you believe. Toobin and the legal system at the time

believed that Hearst, resentful of (but not resistant to) the baggage that came

with wealth, and unhappy in her relationship with her fiancé, welcomed the

opportunity to break away from “the establishment” to establish her own

identity – to the point of breaking laws and participating in deadly actions. After

a lengthy hunt, many close escapes, almost inhuman living conditions, a

horrific gun battle siege of several members of the army, and the eventual

capture of Hearst and her compatriots, Patty claimed in her defense (led by the

famous/infamous Texas attorney, F. Lee Bailey) that she was a victim, was

raped, beaten and starved into submission, and had no choice but to be

complicit with her captors.

Ironically, after condemning her rightwing,

society-driven mother, living with the Symbionese Liberation Army for a year,

and serving 22 months in prison (Commuted by President Jimmy Carter and granted

a full pardon by President Bill Clinton) Patty Hearst married her “pig”

policeman bodyguard, and became very involved in the East Coast society scene. In

2015 her Shih Tzu won the “Toy” category at the Westminster Kennel

Club Dog Show.

If you have any interest in that revolutionary era of our country’s history you will probably enjoy this book.

If you have any interest in that revolutionary era of our country’s history you will probably enjoy this book.

100 Things I Want to Tell My Children And Grandchildren: #22

I know this

is pretty lame compared to the deeply philosophical lessons and stories I typically try to share

in "My 100", but there are just some things that no one ever teaches you to do!

Like how to fold a fitted sheet.

I can’t

tell you how many times I’ve tried to wrestle a fitted sheet into some

semblance of order, and I bet you have too.

So here ya go – one less life-frustration!

You are

welcome.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)